When asked what it takes to speak a foreign language, many will respond that mastering grammar rules is essential. However, behind this truism lies the crucial question of how grammar is mastered and whether knowing a rule means being able to apply it.

Joan Netten and Claude Germain, creators of the NLA method, distinguish between two types of grammar: “internal grammar” and “external grammar“. These pedagogical principles correspond to absolutely different cerebral mechanisms that appeal to two distinct types of memory: declarative memory and procedural memory.

2 memory systems for 2 different grammars

Procedural memory is responsible for implicit skills, those that cannot be explained but can be demonstrated. This skill is present when one no longer needs to make a conscious effort to perform a task, such as repeating a choreography, getting dressed in the morning, or tying one’s shoes. All of this happens automatically, without thinking.

In the language domain, this translates into the correct use of language, automatically, without thinking. This skill is developed through intensive and frequent use of language structures that create patterns at the neuronal level, preferred “paths” for information flows… This is what is called in NLA “internal grammar“. It consists of regularities, is implicit, and non-conscious.

As for declarative memory, it belongs to the conscious domain and contains knowledge about the world. It allows you to know that an apple is a fruit or that the capital of France is Paris. It is also where you will find formal knowledge about how a language works, from vocabulary words to grammar rules and conjugations…

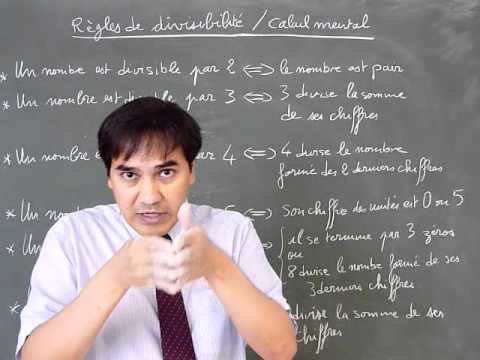

External grammar, therefore, relates to the learning/teaching of rules, tables, and is done using manuals, treatises, or infographics. It is explicit and conscious, and it is the one that language teachers are most familiar with.

The grammatical paradox

The work of Michel Paradis on the double dissociation of Alzheimer’s disease and Broca’s aphasia led to the theorization of the “grammatical paradox” by Claude Germain and Joan Netten.

According to this theory, the two memory systems are independent, and there is no connection between them. This is why “knowing all the rules of how a language works does not necessarily mean being able to speak it, just as it is possible to speak a language perfectly without being able to explain its rules.”

This is a radically different position from that of traditional methods, which postulate that one must first learn the rules, and then do a lot of exercises to transform this knowledge into skill in order to be able to use the language in a conversation naturally and spontaneously.

It is on the recognition of this paradox that NLA proposes absolutely different class activities.

What teaching?

Teachers trained correctly in this method use a set of strategies to first develop strong oral skills in the student. This translates into the almost automatic mastery of structures allowing for the construction of correct sentences, which make sense, and with good pronunciation. This is the stage of establishing a solid internal grammar, which appeals to procedural memory.

Only during the following phases, those of reading and writing, will the teacher provide an observation on the functioning of the language. During this phase, students will analyze certain language phenomena and formulate grammatical principles. This is the phase of conscious analysis, which appeals to declarative memory.

Integrating complementarity

Knowledge of certain principles of brain functioning (of memory) thus gives NLA a status of a balanced method, not rejecting any of the aspects of learning, while giving them their rightful place in terms of importance and timing for their teaching.